Threading Folk and Jazz: Becca Stevens’ Quiet Fire

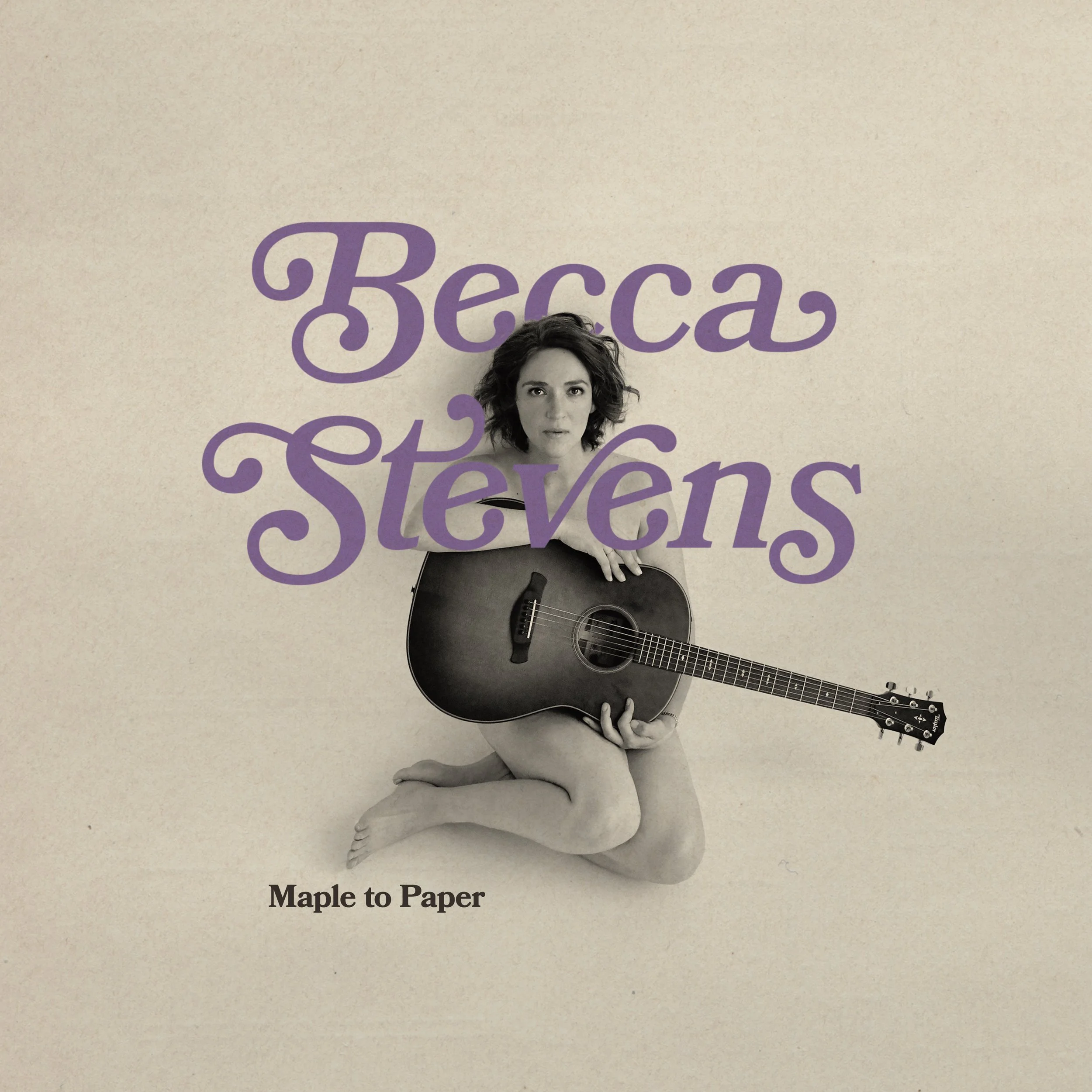

Becca Stevens. Courtesy photo.

Becca Stevens doesn’t treat genre as a fence line. She hears it as a set of threads—folk, jazz, chamber colors—braided for story and feel. In an intimate setting, that braid tightens: voice, guitar, and the listening that lets a melody choose its own light.

“It naturally leads you into a… harmonic direction that you could say is more jazz oriented because you’re no longer in the major chord root, third, fifth… all of a sudden you have like a sus and a sharp 11 and a… flat nine unintentionally,” she says of writing in open tunings. “Because this string is ambiently adding flavor and the shapes that you knew and loved… in an open tuning mean something completely different.”

The roots run back to childhood curiosity more than a conservatory master plan. “When I was a kid, my parents signed me up for a lot of music lessons… I tried my hand at Suzuki violin… then I really took to the flute… and then I was in piano lessons, and for some reason I hated piano lessons,” she remembers. “I felt at a young age that… I wasn’t able to bring my authenticity to those lessons.” The guitar was the switch. “As soon as I touched the guitar… it always felt like a playground to me and a place that was welcoming to my curiosity.”

That curiosity sits at the heart of Maple to Paper, her bare-wire album of voice and guitar recorded live at home. The songs are unguarded, but not fragile; they’re built for the kind of room where you can hear a breath become a phrase. “Some have said listening to it feels almost voyeuristic—like stumbling into a deeply private moment and being invited to stay,” reads the project’s own framing, emphasizing presence over polish and a narrative born of pregnant beginnings, grief, and renewal.

“Now Feels Bigger Than The Past” traces that arc of seeing—how hindsight can change the weight of a memory. “This is one of these songs where the seed of it… came much earlier than the bulk of the writing,” she says. The spark arrived in the days following Prince’s death. “I was grieving that he died and also feeling confused about this effect… someone is fighting to be supported… and then it takes them dying for… an outpouring of love and support on social media… and the streams go up and suddenly people were a fan their whole life.” She kept a single line pinned to a wall for years: What is it about an artist dying that makes the art more palatable? “When I was writing the music for Maple to Paper, I was thinking about my mom… diagnosed with… terminal cancer… and I was thinking, wouldn’t that be an interesting place to land gracefully?” Verse by verse, the song widens that thesis—artist, betrayer, mother—until it lands close to home. “The third verse is for my mom and also for my daughter, who was in my belly at the time.”

If that track opens a window on time and grief, “I’m Not Her” stares down the mirrors we invite into our pockets. “The ideas and words came first,” Stevens says, describing a craft exercise she gives her songwriting students: build a bridge from the thing you want to do to the thing you need to do. “Feed the urge… and then create a bridge back to the thing that you ought to be doing,” she explains—collecting images from everyday life, cutting them up like puzzle pieces, moving them around the wall “like lyrics.”

“So ‘I’m Not Her’ started that way. I was depressed and scrolling through Instagram and comparing myself to other women influencers,” she says. The first draft had “like 10 different women,” later narrowed to two, giving space for “the dark, twisted, cynical sense of humor that doesn’t often come through” in her songs. Then the guitar arrived and pulled alongside the lyric. “Once the guitar came in… they were working together and driving… in the front seat together for sure.”

Stevens brings the same plain-spoken clarity to a conversation the industry often treats as a footnote: what it takes to tour as a mother. “Money,” she says first, then adds the rest of the ledger: “time and money and energy.” The arithmetic rarely balances. “You have children and then you want to be with them, and then if you can’t be with them, you have to pay to not be with [them]… and if you are with them on the road, then you’re paying physically for… the toll that that takes on the body and… on their bodies too.” The choices are personal and ongoing. “Is it worth it to me to keep my career fire burning while also taking good care of these little humans?… Each person has to figure out what that looks like for them.”

The most challenging stretch, she says, can be the first year. “It is like the hormones and the sleep deprivation and the feeling that the world just doesn’t get it,” compounded by an artist identity that “inevitably [gets] stripped away… and then you look in the mirror and you don’t recognize yourself.” That’s why she keeps talking—peer to peer, parent to parent—about resources, realism, and that missing sense of community. “Connecting those dots back together is something that I’m really passionate about… I’ve been through it twice, and I want to help.” Progress? “A little… We’ve got a ways to go.”

The artistic through-line binding these subjects—harmony games, identity, care—isn’t conceptual so much as practical. Open strings invite colors that lyrics can answer. A “close-at-hand” mic image turns a living room into a stage. A song that began with a scrap of paper becomes a map for grief. In the small room, the choices aren’t hidden by volume.

Stevens’ collaborative world hints at why those choices land with such poise. She’s moved with (and learned alongside) artists who treat song as a flexible instrument—David Crosby’s Lighthouse Band, Attacca Quartet, and peers who prize arrangement as expression, not adornment. Maple to Paper presents that fluency at its most elemental: “voice, guitar, and the alchemy of presence.”

But the proof is in the performing. In a focused room, Stevens’ material asks for your quiet and offers its own. The invitation is plain in the way she talks about process—build a bridge, move the pieces, follow the shape that wants to speak—and in the candor with which she names the costs of making art while mothering. The result is not an argument for austerity; it’s an argument for intention.

“I often regret not sticking with the piano,” she admits with a smile, “but as soon as I touched the guitar… it always felt like a playground.” The playground is still open. The games are deeper now. The harmonies are brighter for the open strings, the stories braver for the life that touches them, and the songs—especially in close quarters—are made to be heard as if they’re happening for the first time.

Show Information — Joe Henderson Lab (San Francisco)

· Event: Becca Stevens

· Where: Joe Henderson Lab at SFJAZZ Center

· When: October 14–15 (four shows, two nightly)

· Showtimes: 7:00 p.m. & 8:30 p.m.

· Tickets: https://www.sfjazz.org/

· Artist website: https://beccastevens.com

Editor’s note: Quotes have been lightly edited for clarity and length.